Join the AI Workshop to learn more about AI and how it can be applied to web development. Next cohort February 1st, 2026

The AI-first Web Development BOOTCAMP cohort starts February 24th, 2026. 10 weeks of intensive training and hands-on projects.

WebRTC stands for Web Real Time Communication.

It allows to create a direct data communication between browsers.

You can use it to

- stream audio

- stream video

- share files

- video chat

- create a peer-to-peer data sharing service

- create multiplayer games

and more.

It’s an effort to make real-time communication applications easy to create, leveraging Web technologies, so that no 3rd party plugin or external technology is needed beside your Web browser.

There should be no need for a plugin to perform RTC in the future, but all should instead rely on a standard technology - WebRTC.

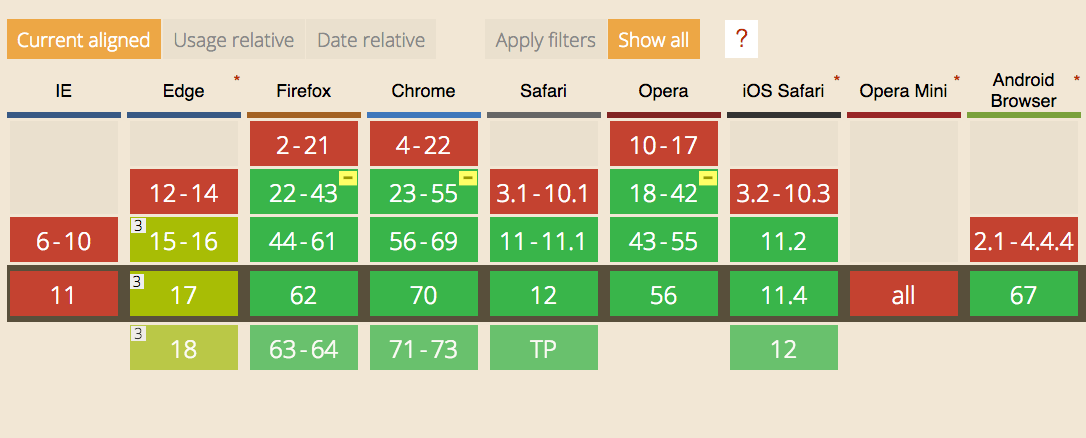

It is supported by all the modern browsers (with partial support from Edge which does not support RTCDataChannel - see later):

WebRTC implements the following APIs:

MediaStreamgets access to data streams from the user’s end, like the camera and the microphoneRTCPeerConnectionhandles communication of audio and video streaming between peersRTCDataChannel: handles communication of other kinds of data (arbitrary data)

With video and audio communication you’ll use MediaStream and RTCPeerConnection.

Other kind of application, like gaming, file sharing and others rely on RTCDataChannel.

In this article I’ll create an example using WebRTC to connect two remote webcams, using a Websockets server using Node.js.

Tip: in your projects you’ll likely use a library that abstracts away many of those details. This tutorial aims to explain the WebRTC technology, so you know what is going on under the hood.

MediaStream

This API lets you access the camera and microphone stream using JavaScript.

Here is a simple example that asks you to access the video camera and plays the video in the page:

See the Pen WebRTC MediaStream simple example by Flavio Copes (@flaviocopes) on CodePen.

We add a button to get access to the camera, then we add a video element, with the autoplay attribute.

We also add the WebRTC Adapter which helps for cross-browser compatibility:

<button id="get-access">Get access to camera</button>

<video autoplay></video>

<script src="https://webrtc.github.io/adapter/adapter-latest.js"></script>The JS listens for a click on the button, then calls navigator.mediaDevices.getUserMedia() asking for the video.

See the getUserMedia() tutorial

Then we access the name of the camera used by calling stream.getVideoTracks() on the result of the call to getUserMedia().

The stream is set to be the source object for the video tag, so that playback can happen:

document

.querySelector('#get-access')

.addEventListener('click', async function init(e) {

try {

const stream = await navigator.mediaDevices.getUserMedia({

video: true,

})

document.querySelector('video').srcObject = stream

document.querySelector('#get-access').setAttribute('hidden', true)

setTimeout(() => {

track.stop()

}, 3 * 1000)

} catch (error) {

alert(`${error.name}`)

console.error(error)

}

})The arguments of getUserMedia() can specify additional requirements for the video stream:

navigator.mediaDevices.getUserMedia(

{

video: {

mandatory: { minAspectRatio: 1.333, maxAspectRatio: 1.334 },

optional: [{ minFrameRate: 60 }, { maxWidth: 640 }, { maxHeigth: 480 }],

},

},

successCallback,

errorCallback,

)To get an audio stream you would ask for the audio media object too, and call stream.getAudioTracks() instead of stream.getVideoTracks().

After 3 seconds of playback we stop the video streaming by calling track.stop().

Signaling

Signaling is not part of the WebRTC protocol but it’s an essential part for real time communication.

Via signaling, devices communicate between each other and agree on the communication initialization, sharing information such as IP addresses and ports, resolutions and more.

You are free to choose any kind of communication mechanism, including:

We implement it using Websockets.

Install ws using npm:

npm init

npm install wsWe start with a simple Websockets server skeleton:

const WebSocket = require('ws')

const wss = new WebSocket.Server({ port: 8080 })

wss.on('connection', (ws) => {

console.log('User connected')

ws.on('message', (message) => {

console.log(`Received message => ${message}`)

})

ws.on('close', () => {

//handle closing

})

})We first add a ‘username’ box to our frontend, so the user can pick a username before connecting to the server.

<div id="login">

<label for="username">Login</label>

<input id="username" placeholder="Login" required="" autofocus="" />

<button id="login">Login</button>

</div>In the client JavaScript we initialize the Websocket to the server:

const ws = new WebSocket('ws://localhost:8080')

ws.onopen = () => {

console.log('Connected to the signaling server')

}

ws.onerror = (err) => {

console.error(err)

}When the user enters the username and clicks the login button we get the username value and we check it, then we send this information to the server:

document.querySelector('button#login').addEventListener('click', (event) => {

username = document.querySelector('input#username').value

if (username.length < 0) {

alert('Please enter a username 🙂')

return

}

sendMessage({

type: 'login',

username: username,

})

})sendMessage is a wrapper function for sending a JSON-encoded message to the Websocket server. We use a type parameter to separate different kind of messages we’ll send:

const sendMessage = (message) => {

ws.send(JSON.stringify(message))

}Server side, we decode the JSON message and we detect the message type

ws.on('message', (message) => {

let data = null

try {

data = JSON.parse(message)

} catch (error) {

console.error('Invalid JSON', error)

data = {}

}

switch (data.type) {

case 'login':

console.log('User logged', data.username)

break

}

})We must add the user to a list of connected users, stored in an associative array users:

const users = {}If there is another user already with this same username, we send an error to the client, otherwise we add the user to the array, storing the Websocket connection:

//...

case 'login':

console.log('User logged', data.username)

if (users[data.username]) {

sendTo(ws, { type: 'login', success: false })

} else {

users[data.username] = ws

ws.username = data.username

sendTo(ws, { type: 'login', success: true })

}

breakClient-side, when this happens we handle the message and we call the getUserMedia() function:

ws.onmessage = (msg) => {

console.log('Got message', msg.data)

const data = JSON.parse(msg.data)

switch (data.type) {

case 'login':

handleLogin(data.success)

break

}

}handleLogin() checks if the login was successful, and if so it initializes the RTC connection:

const handleLogin = (success) => {

if (success === false) {

alert('Login failed, try a different username')

} else {

document.querySelector('div#login').style.display = 'none'

document.querySelector('div#call').style.display = 'block'

startRealTimeCommunication()

}

}At this point we must dive into how RTCPeerConnection works.

RTCPeerConnection

RTCPeerConnection is at the basis of establishing a WebRTC connection between two peers.

It accepts a configuration object that contains the STUN or TURN (or both) servers info we use.

These are needed to communicate to the user the IP address of its machine, as the client is behind a NAT router. Most users do not connect directly using a modem.

If you’re not familiar with NAT, very quickly: your house has one external IP address given to you by the provider, and your router has an internal IP address (like 192.168.x.x or 10.0.x.x). Every device connected to the router gets an internal IP address too. The router uses NAT to translate external IP addresses to internal IP addresses, and back.

We’ll use the Google STUN servers that are free to use:

const configuration = {

iceServers: [{ url: 'stun:stun.l.google.com:19302' }],

}First we request access to the camera using getUserMedia():

const startRealTimeCommunication = () => {

navigator.getUserMedia(

{ video: true, audio: true },

(myStream) => {

stream = myStream

document.querySelector('video#local').srcObject = stream

connection = new RTCPeerConnection(configuration)

},

(error) => {

console.error(error)

},

)

}Once we have a stream, we can create an RTCPeerConnection and we also initialize a callback for when a stream is added from the other remote end. We do this in this way to provide compatibility with implementations that don’t use track-based events yet, like Firefox and Safari:

const startRealTimeCommunication = () => {

navigator.getUserMedia(

{ video: true, audio: true },

(myStream) => {

stream = myStream

document.querySelector('video#local').srcObject = stream

connection = new RTCPeerConnection(configuration)

connection.addStream(stream)

connection.onaddstream = (e) => {

document.querySelector('video#remote').srcObject = e.stream

}

},

(error) => {

console.error(error)

},

)

}At this point we have a connection to the server through Websockets, and we are ready to negotiate the WebRTC session with the remote peer.

To call the other peer we need to know their username, so we add a text field and button to start the call:

<div>

<input id="username-to-call" placeholder="Username to call" />

<button id="call">Call</button>

<button id="close-call">Close call</button>

</div>In the client JavaScript we listen for the click event on this button and we get the username value.

If the username is valid we store it in the otherUsername variable we’ll use later, and we create an offer.

let otherUsername

document.querySelector('button#call').addEventListener('click', () => {

const callToUsername = document.querySelector('input#username-to-call').value

if (callToUsername.length === 0) {

alert('Enter a username 😉')

return

}

otherUsername = callToUsername

// create an offer

connection.createOffer(

(offer) => {

sendMessage({

type: 'offer',

offer: offer,

})

connection.setLocalDescription(offer)

},

(error) => {

alert('Error when creating an offer')

console.error(error)

},

)

})Once we get the offer by calling RTCPeerConnection.createOffer(), we pass it to our server and we call RTCPeerConnection.setLocalDescription() to configure the connection.

On the server side, we process the offer and we send it to the user that we want to connect to, passed as data.otherUsername:

case 'offer':

console.log('Sending offer to: ', data.otherUsername)

if (users[data.otherUsername] != null) {

ws.otherUsername = data.otherUsername

sendTo(users[data.otherUsername], {

type: 'offer',

offer: data.offer,

username: ws.username

})

}

breakThe client receives this offer as a Websocket message, and we call the handleOffer method:

ws.onmessage = (msg) => {

//...

switch (data.type) {

//...

case 'offer':

handleOffer(data.offer, data.username)

break

}

}This method accepts the offer and the username, and we first call RTCPeerConnection.setRemoteDescription() to specify the properties of the remote end of the connection, then RTCPeerConnection.createAnswer() to create the answer to the offer.

Once the answer is created, we use it to set the properties of the local end of the connection and we post it to our server, using the sendMessage function.

The RTCSessionDescription object describes the connection capabilities and must be initialized before the RTC can happen. We must set both the description of the local end of the connection (setLocalDescription), and the description of the other end of the connection (setRemoteDescription).

const handleOffer = (offer, username) => {

otherUsername = username

connection.setRemoteDescription(new RTCSessionDescription(offer))

connection.createAnswer(

(answer) => {

connection.setLocalDescription(answer)

sendMessage({

type: 'answer',

answer: answer,

})

},

(error) => {

alert('Error when creating an answer')

console.error(error)

},

)

}On the server side we handle the answer event:

case 'answer':

console.log('Sending answer to: ', data.otherUsername)

if (users[data.otherUsername] != null) {

ws.otherUsername = data.otherUsername

sendTo(users[data.otherUsername], {

type: 'answer',

answer: data.answer

})

}

breakWe check if the username we want to talk with exists, then we set it as the otherUsername of the Websocket connection. We send the answer back to that user.

On the client side that user will get the answer message that triggers the handleAnswer() method, which calls RTCPeerConnection.setRemoteDescription() to synchronize the properties of the remote end of the connection:

ws.onmessage = (msg) => {

//...

switch (data.type) {

//...

case 'answer':

handleAnswer(data.answer)

break

}

}

const handleAnswer = (answer) => {

connection.setRemoteDescription(new RTCSessionDescription(answer))

}Now that the session descriptions have been synchronized, the two peers start to determine how to establish the connection between them, using the ICE protocol. This is the key part that works around the NAT routers limitations.

RTCPeerConnection produces an ICE candidate and calls its onicecandidate callback function. In the callback we send the ICE candidate to the other end of connection, using our sendMessage() function:

connection.onicecandidate = (event) => {

if (event.candidate) {

sendMessage({

type: 'candidate',

candidate: event.candidate,

})

}

}On the server side we handle the candidate event by sending it to the other peer:

//...

case 'candidate':

console.log('Sending candidate to:', data.otherUsername)

if (users[data.otherUsername] != null) {

sendTo(users[data.otherUsername], {

type: 'candidate',

candidate: data.candidate

})

}

breakThe other peer receives it on the client:

ws.onmessage = (msg) => {

//...

switch (data.type) {

//...

case 'candidate':

handleCandidate(data.candidate)

break

}

}

const handleCandidate = (candidate) => {

connection.addIceCandidate(new RTCIceCandidate(candidate))

}We call RTCPeerConnection.addIceCandidate() to add the candidate locally.

At this point the ICE exchange steps and session description are complete, negotiation is done and WebRTC can connect the two remote peers, using the connection mechanism that was automatically agreed upon.

We now have 2 computers directly communicating to each other exchanging their webcam streams!

Closing the connection

The connection can be closed programmatically. We have a button “Close call” that we can click once the connection has been made:

<button id="close-call">Close call</button>document.querySelector('button#close-call').addEventListener('click', () => {

sendMessage({

type: 'close',

})

handleClose()

})

const handleClose = () => {

otherUsername = null

document.querySelector('video#remote').src = null

connection.close()

connection.onicecandidate = null

connection.onaddstream = null

}On the client side we remove the remote streaming and we close the RTCPeerConnection connection, setting the callback for its events to null.

We send the close message to the server, which in turn sends it to the remote peer:

case 'close':

console.log('Disconnecting from', data.otherUsername)

users[data.otherUsername].otherUsername = null

if (users[data.otherUsername] != null) {

sendTo(users[data.otherUsername], { type: 'close' })

}

breakso in the client side we can call the handleClose() function:

ws.onmessage = (msg) => {

//...

switch (data.type) {

//...

case 'close':

handleClose()

break

}

}The complete example is available on this Gist:

Lessons in this unit:

| 0: | Introduction |

| 1: | getUserMedia |

| 2: | ▶︎ WebRTC |

| 3: | What to do if WebRTC on iOS shows a black box |